Missing Middle Models: Planning for Equity

In our role on housing projects in Pittsburgh, a legacy city, and Bozeman, a strong Mountain Region market, evolve continues to be invested in the search for the key characteristics of what might help meet the need for missing middle housing.

We discussed with our partner, Christine Walker of Navigate LLC, the strategies involved in establishing and operating a Community Land Trust to address housing needs and long-term affordability.

Sarine: What are the challenges and opportunities cities and towns in the Mountain Region face as they try to accommodate increased housing needs at this time?

CW: Mountain West cities face multifaceted challenges as they try to accommodate population growth, due mainly to the increase in remote workers moving to these areas. First, is the high construction cost and lack of a large local labor pool. Second, is the limited number of local developers who produce housing at scales to meet the demand. Third, is the continued tension between development, mostly single family detached homes on large lots, and land conservation due to the regional and national significance of the natural resources in these areas. Finally, the aesthetics of the development matter. When you cannot tell if you are in Bozeman, Houston, Pittsburgh, or Portland, then the development is not responding to the local conditions or the desires of the community. Density causes a concern of moving away from the community character and sense of place, which directly impacts the “desirability” of a place.

The opportunities are the flipside of the challenges. First, there’s opportunities for more production builders to set up shop in the region. Second, using land more wisely would help bridge the tension between development and land conservation. Third, some local contractors are capitalizing on growing the local labor pool by focusing on training and educating more people to go into the trades.

There is also an opportunity to learn from successful projects that have tried to balance all these aspects. Once you factor in climate change, community health concerns, and the need to balance the challenges with the opportunities, it is clear that housing has to be a strategic investment in place and community and not just a roof over your head. Instead let’s look at strategically investing in creating really great opportunities for people to thrive in the place that they live.

Sarine: How does design factor into this conversation? What were the successful design strategies that came out of the Bridger View project that helped create that sense of place you mention.

CW: Even strong markets can suffer from a lack of investment in good design and placemaking. A critical opportunity is engaging the design community to create great places and great neighborhoods. I think design can help communities continue to be desirable for not only those coming to the community but people who are already living in that place.

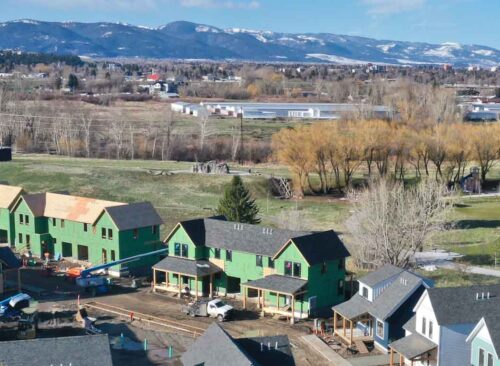

With the Bridger View project in Bozeman, Montana, we invested in site design which is usually something that is overlooked when designing a neighborhood. Not just looking at the homes but also how the homes interacted with the public realm. I think that was the most important and what that resulted in was creating a human-scaled compact neighborhood that used land more wisely. With this project, it was necessary that the housing connect with Story Mill Park as a community amenity and would continue to add value twenty years down the line. We spent a lot of time in the front end to figure out what we wanted to see in concept and freed the designers from worrying about codes to focus on designing a great neighborhood. We also applied sustainability, with an eye on energy efficiency to create permanent affordability over time. Sustainability also led to a higher quality product which has resonated with anyone walking through the homes. I think it is the wave of the future and we have attracted socially conscious buyers who are interested in that. The emphasis on sustainability allowed us to achieve a healthier living environment for the long term.

Sarine: How does equity factor into the work in Bozeman and with organizations like the Trust for Public Land?

CW: In Bridger View, we built smaller units that ended up demanding a lower price rate. We call it “below market”, because affordability can be seen, as by 99% of the country, as a low-income tax credit multi-family product. Also affordability begs the question ‘affordable for who?’ There is room for terms like housing for middle-income residents, housing that people can afford at or below market. The main message is that it’s not a for-profit enterprise. This is where our partners such as the Headwaters Community Housing Trust and Jon Catton, our communications consultant, help ensure that the project objectives are communicated well.

On equity, one of the most exciting pieces of the Bridger View neighborhood is that we fully integrated the below-market homes with the market-rate homes. There is absolutely no distinction between them. What we’ve found is that building to the same design and standards ended up being more cost-effective. When we compromise on quality, it impacts the health of the residents and our climate goals. Although in Bozeman there isn’t as much diversity in the demographics, there are disparities in income level and access to opportunities. Another way the project and the Headwaters Community Housing Trust is addressing equity, is through a weighted drawing process. Additional weight in the selection process is given to applicants who have been living in the community for 5 years or more, to balance out the influx of remote workers who are earning more. Most community land trusts set up a waitlist, and we find that people with means tend to know and hear about these opportunities more than those with less means. Which is why a weighted drawing system better addresses equity concerns and making sure we are making the opportunity widely known. I think Headwater Community Housing Trust has also made a concerted effort to be a very diverse board, more so than I’ve seen in any other non-profit board in the community, to bring different perspectives to the conversation about how we create housing opportunities for our middle-income residents in Bozeman.

Sarine: Any final thoughts?

CW: I would say intentionally setting really good goals for the project from the beginning, narrowing that down to design intents and then getting the right team on board is very important. Changing the way things are typically done is a constant struggle, especially in the design and construction industry which is pretty entrenched in certain ways of doing things. With projects like Bridger View we are hoping to show people another way of providing housing and empowering them.

To ensure you get to read our latest stories, subscribe to our evolve insights newsletter.