Missing Middle Models: Finding Opportunities in Legacy Cities

Authored by Christine Mondor with contributions from Ashley Cox & Daniel Klein

There is a buzz around Missing Middle homeownership.

The term, popularized by Dan Parolek, is often used to describe a mix of housing types that are integrated into neighborhood—including ADUs, townhouses, small to medium scale multiunits, and even single family units. The mix of units allows a mix of incomes, lifestyles, etc., and while often found in legacy neighborhoods, is rarely created by modern zoning or masterplanned districts. Physical form is but one part of a complex ecosystem where missing middle housing is an endangered species.

In addition to a formal typology, missing middle is also a demographic that is underserved in the current market. Missing middle describes a segment of the population that is not considered low income or high income—households that make between 80-120% of an area’s average median income. In communities across the country, there are few missing middle units produced as the missing middle cannot draw upon affordable housing subsidy programs and the unit costs lack financial return of luxury housing .

Why care about the missing middle segment when there is so much need for affordable housing? Without missing middle housing, people cannot climb the housing accessibility ladder as there are missing rungs and they are unable to move from different levels of home ownership or rental product as their households grow or contract. This is especially acute in midsize and smaller markets like Denver, Detroit, Buffalo, and Pittsburgh, that have been bastions of affordability with their aging housing stock.

In our new series, Missing Middle Models, we break down the reasons why Missing Middle Housing is needed, challenges in the way of producing more of these housing types, and different strategies to address the need.

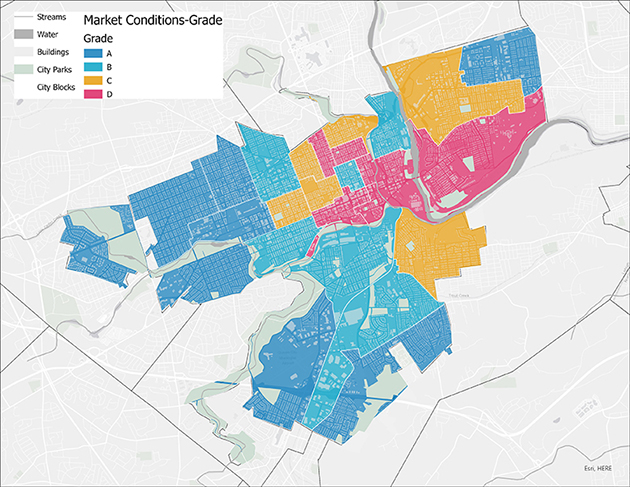

Doughnut economics

The city of Allentown PA identified affordable housing as part of their comprehensive plan priorities and asked us to assess housing needs and opportunities in a follow up 2021 Housing Study. During the Comprehensive Plan process, the city found that many working class families had to leave and commute for lack of adequate housing choices within the city, often described as the “doughnut effect”. When development around the edges of the city becomes stronger than the center, property values in the city center drop and this disincentivizes property owners from keeping up with maintenance over time. Similar to many other urban centers in the late twentieth century, we have seen a decline in overall maintenance and rehabilitation of older housing that has become undesirable or uninhabitable. While this phenomena often created what we call “naturally occurring affordable housing,” they can become inaccessible to those who need them most as middle income families are forced to compete for those same units. Cities like Allentown want to meet the housing gap for this often overlooked segment of the housing market, thus the city carried on after completion of the comprehensive plan to conduct a housing trust feasibility study.

Taking on the myth of naturally occurring affordable housing

Affordable housing metrics focus on new unit production. The 17,000 units referenced in Pittsburgh’s 2016 Housing Study served as a concrete call to action to build new affordable housing; it also created a blind spot to the thousands of existing under-invested or vacant houses. The report’s assertion that middle-income households were served by this inventory of naturally occurring affordable housing (NOAH) also enabled a false sense of security. Pittsburgh’s NOAH is affordable only because it is under-maintained or held artificially low due to lack of neighborhood desirability (2016 Pittsburgh Housing Needs Assessment). There are complex forces that make this true, and focusing on the existing housing stock is key to reach a diverse housing ecosystem that serves low, middle, and upper incomes.

The average Pittsburgh home was built in 1920 with renovation costs that can easily rise above the missing middle range. With few programs or funding streams available for legacy buildings and neighborhoods, renovation becomes a narrow option. Consider the current calculus of homeowner-led renovation—in weak market neighborhoods, you might be able to purchase a house for $100k to $150K. Assuming the house will appraise and a homeowner can get a loan, they can easily spend an estimated range of $200k to $250,000 for quality improvements and renovation costs may range from $300k to $400,000 to create a middle income unit. As the neighborhood improves, low-cost units are harder to find and the math only gets worse

Indirect costs are challenging as well. Pittsburgh’s contractors cater to the larger markets of affordable housing and luxury housing, with few enterprises suited for the scope and scale of moderate-income homeowner renovation. The costs associated with sweat equity are not to be underestimated. The time, knowledge, and capacity to manage a complex renovation project can be daunting and there is little education or professional support for such homeowners. The direct and indirect costs combine to make the turnkey exurban unit quite attractive and those who can, move, exacerbating the economic doughnut effect in the Pittsburgh area.

So what kinds of strategies can cities turn to in order to change this trend?

Our series will examine three categories of strategies:

DESIGN & CONSTRUCTION. One of the biggest drivers of housing affordability is the cost of building and maintaining the housing units and shared neighborhood infrastructure themselves. Design strategies can help us build more units at a lower cost, theoretically resulting in savings for owners and renters. It’s also important to consider the costs involved with maintaining each unit, and operating its utilities. Design innovations can enable long-term affordability by lowering those costs, influencing many aspects of design like unit size, resource efficiency, construction materials, incorporating more common amenities, thinking about walkability and access to mass transit and also the construction processes used in the buildings.

ECONOMIC STRATEGY. The economy is a major force impacting regional housing markets, and there are a variety of innovations for enabling increased home ownership: Community Land Trusts, Co-Ops, Tax Credits, and Housing Funds are some of the economic tools that cities and neighborhoods have deployed. As economic principles like Supply & Demand underpin the housing market, is it safe to assume that design & construction methods and policy interventions are always linked to economics as well?

POLICY. On the policy side, we will look at how zoning and other types of legislation and regulation has shaped our current housing landscape. What’s next in the world of housing and development policy, and where are we seeing new kinds of intervention in support of Missing Middle Housing? What has been the impact of Inclusionary Zoning in different regional contexts?

To ensure you get to read about these strategies and see case studies we’ve selected from cities across the United States, make sure you’re subscribed to our evolve insights newsletter.