Living Buildings as Regional Hubs for Sustainable Redevelopment

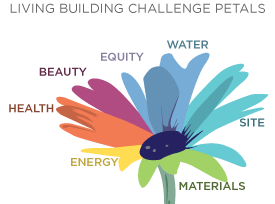

Imagine buildings that are able to produce all of the energy they need using renewable sources such as wind or solar, that capture and treat all of the water needed for building occupants and systems, eliminating the need for water or sewage treatment infrastructure. Mounting evidence suggests that buildings of the future must look like this to secure a sustainable future. The Living Building Challenge (LBC) is leading the charge by requiring these attributes of projects that are seeking its prominent certification. And as cities and towns transition to green building and sustainable living, we look to Living Buildings for inspiration.

The new Center for Sustainable Landscapes (CSL) at Phipps Conservatory, with evolveEA’s guidance, is pursuing the LBC and will be one of the largest certified Living Buildings in the world. By demonstrating sustainability principles and acting as an educational hub for those interested in learning more; the CSL has become an important anchor project not just for Pittsburgh, but also for green buildings globally. With a project schedule that began back in 2007, it has also served as a model for how time-intensive and truly collaborative the process must be.

Since the project’s inception, we have noticed an increase in the number of building projects that are pursuing the LBC, and we are currently involved in other Living Building projects such as the Frick Environmental Center in Pittsburgh, and the Living Lab at Purdue University’s Ross Biological Reserve. Given the complexity of these projects, we have found that it is not only an opportunity, but an imperative to provide education and build consensus among the design team and each project’s community of stakeholders regarding sustainability.

Building Consensus

At evolveEA we start this process by facilitating a community charrette, guiding participants through a series of thinking exercises in order to define goals and flesh out the scope of the project. In a recent charrette we asked the community about its resources and knowledge in order to create a stakeholder map. At Phipps Conservatory, the CSL’s purpose as a sustainable cornerstone touching multiple local and even global communities informed the design process. Identifying resources, formulating a vision and prioritizing goals guided the design and building process. Project outcomes focused on connecting people to the place through experiential and tactile learning.

Phipps Conservatory has long been a prominent institution, special to the Pittsburgh region and beyond ever since its iconic glass greenhouse was constructed in 1893. Already home to a thriving community, by taking on a national leadership role in green building, Phipps has become not only one of the greenest institutions in the country, but an inspiring realization of harmony between human beings and the natural world. The design of the CSL has been driven by a community of stakeholders: the champions of the effort who advocate tirelessly for advancement from within the organization, the public who visit and support Phipps, and a diverse team of professional advisors.

Living Buildings as Laboratories

When completed, LBC projects are not just buildings; they are living organisms and laboratories for testing and experiential learning that encompass the built environment and an entire community. What has become evident during these projects is that the opportunity for engagement does not disappear once construction is complete. In fact, that is just the beginning, and some of the deepest value we see in Living Buildings is their ability to inspire through physical demonstration and to teach principles of design, science and math in an innovative learning environment; these opportunities occur throughout the project lifecycle, and are especially valuable after design and construction as the project opens to the public.

Big or small, Living Buildings have the power to shift the dialogue concerning humans and the ways in which we interface with our built environment. They allow us to ask difficult and challenging questions concerning what is truly possible in our home, office, or community. They change the way people relate to places, ultimately redefining the human experience within a larger ecological context. They truly are hubs for new ideas around the future of sustainable redevelopment.