Top-Down/Bottom-Up

Every year in Pittsburgh, the SoArch Lectures Series, organized by Carnegie Mellon University’s School of Architecture, hosts lectures by well-established architects from the US and beyond who are leaders in design and sustainability. The last SoArch lecture recently took place at the Carnegie Museum of Art, where the presenting architect was Peter Busby, the Principal Managing Director of Perkins+Will in San Francisco. After the merger of his firm with Perkins+Will in 2004, he became leader of the firm’s Sustainable Design Initiative. His work emphasizes regenerative planning and sustainable communities, and since his work is related to our own Ecodistrict planning, we were excited to see their latest projects and ideas.

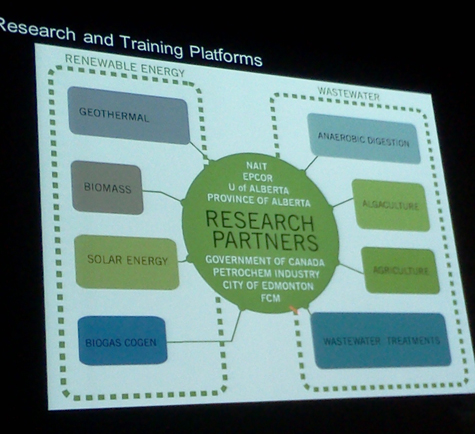

From Busby’s presentation, the two projects that relate to regenerative planning were the Dockside Green development and Edmonton ConnectiCity. Both projects show remarkable achievements on sustainable development principles as well as innovations in district infrastructures. Dockside Green in Victoria, BC is a well renowned sustainable redevelopment project. It integrates systems of water management and wastewater treatment, biomass heat generation (from wood scrap), energy and water conservation, alternative transportation and many others. The project is implemented in three phases, and currently it has reached phase two with LEED Neighborhood Development Platinum Designation. Edmonton’s Connecticity’s development plan includes some of the Dockside’s sustainable innovations and even more; the project is designed to go beyond carbon neutral and they are including dedicated areas of land for urban agriculture. ConnectiCity is based on a four-prong approach: “Connect to communities”, “Connect to growth”, “Connect to history and “Connect to nature”.

Slide from the presentation showing the areas of research in the new neighborhood. The systems shown are part of the redevelopment proposal.

The remarkable part for both of those projects is the opportunity to integrate complicated infrastructures for food, water, waste and energy under one plan and benefit from the synergies this integration provides; achieving carbon neutrality, using organic waste as fertilizer, reusing wastewater for irrigation, using heat and energy produced from sewage treatment and organic waste and so on. The projects highlight the benefits of integrated design by an interdisciplinary team. And by taking a look at Dockside Green, we can see that these are not redevelopment plans that just stay on paper.

However, an important part of sustainable development that those projects are not addressing as successfully is the social aspect, something most top-down design approaches neglect. In general, social sustainability comes last among the three main parts of sustainable development, with economic and environmental sustainabilities being the driving goals. (Colantonio, 2009) .

But what exactly is social sustainability? After a small amount of research, I found the following definition that includes one really important part of the social aspect neighborhood planning often left out of the process: the participation.

“…a quality of societies. It signifies the nature-society relationships, mediated by work, as well as relationships within the society. Social sustainability is given, if work within a society and the related institutional arrangements satisfy an extended set of human needs [and] are shaped in a way that nature and its reproductive capabilities are preserved over a long period of time and the normative claims of social justice, human dignity and participation are fulfilled.” (Littig, Grießler, 2005)

It is indeed quite difficult to measure the social sustainability aspect and provide performance indicators for a specific project. As the environmental and economic benefits of a development can be more easily projected and grasped, top-down developments provide a more clear picture for those aspects rather than the social one. However, over the last few years the need for social indicators has led planners and designers to look at certain metrics for their proposed projects such as: job generation, income levels, decrease in poverty levels and increase in safety, food safety, access to education, health and recreation, and similar statistical data. For example the Human Development Index (HDI) is an index that measures development based on life expectancy, educational attainment and income. (“United Nations Development Programme (UNDP),” 1990) Unfortunately, all the above metrics do not address social participation and engagement, which is really critical to the success of a redevelopment project.

The projects of architects, planners and designers using the top-down approach always have the risk of failure embedded in them. Even the project with the best intentions can fall short socially, and be rejected by the community. A sad example of that is the design of an “Ecocity” by William McDonough at Huangbaiyu, China. This masterplan by the green building leader well-known for his cradle-to-cradle innovations, included a lot of great features related to food, water and energy. However, due to lack of understanding the local community and their way of living, as well as poor communication with them, the realized masterplan stays currently empty and rejected by the community. (Stone, 2006) So, then how “eco” is a “city” that lays empty in the middle of nowhere?

View of the Huangbaiyu project

All of the above trigger my interest, as we strive for success through an Ecodistrict planning framework oriented towards the opposite approach: the bottom-up. Bottom-up sustainable development intends to organize and energize independent neighborhood initiatives under a common vision and mission. The most critical and challenging part of a bottom-up approach is to build community capacity in order to take action, realize projects and help communities revitalize their own neighborhoods. Nevertheless, projects that are based on a bottom-up approach still face challenges. Limited funding and resources lead to failure of projects’ implementation or to long-lasting procedures with few short-term achievements. That usually has a negative impact on a community’s motivation as they have the need to see their work come to fruition.

Another difficulty for the bottom-up approach can be conflicting interests within a community. There is an understandable embedded complexity in uniting people from different backgrounds and with different interests under the same vision. Recently, in Pittsburgh the long-awaited Business Improvement District (BID) for the Lawrenceville neighborhood was defeated. This initiative from the Lawrenceville Corporation, would have implemented the collection of a small fee from business owners and operators inside a defined district, concentrating funds within the neighborhood in order to advance marketing initiatives and an enhanced streetscape to help boost the local economy. The BID would increase property values in the neighborhood and keep quality tenants while attracting more customers. Unfortunately, conflicting interests between the owners of different types of businesses led to the defeat of the initiative. (Nelson, 2013)

Our communication design work for the Lawrenceville Corporation to brand and promote the BID as a valuable investment for the neighborhood

Taking all this into account, I cannot help but wonder how we can use the benefits of a top-down approach—stable and secure funding, organized initiatives and systems, research and innovation—in combination with the qualities of bottom-up community planning—social engagement, building community capacity and ensuring long-term participation in community initiatives. As designers in the field of sustainability, how can our dreams of ecocities include active social participation rather than only social imagination? How can professionals best work with communities to advance sustainability?

References:

Colantonio, A. (2009). Social Sustainability: Linking Re search to Policy and Practice. Oxford Institute for Sustainable Development. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/research/sd/conference/2009/papers/7/andrea_colantonio_-_social_sustainability.pdf

Nelson, D. (2013, February). Realtors group rallies against Lawrenceville BID tax – Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Pittsburgh post-Gazette. Retrieved April 28, 2013, from http://www.post-gazette.com/stories/local/neighborhoods-city/realtors-group-rallies-against-lawrenceville-bid-tax-676400/

Stone, R. (2006). DEVELOPMENT AND ECOLOGY: Villagers Drafted Into China’s Model of “Sustainability.” Science, 312(5770), 36a–36a. doi:10.1126/science.312.5770.36a

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (1990). Retrieved April 28, 2013, from http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics/hdi/