Artists and Neighborhood Change

Last month I took a bus trip from Pittsburgh to Baltimore, Maryland to attend a conference called Artists and Neighborhood Change. The topic of community outreach and engagement through the arts has captivated me over the past several years, as a practicing artist, an urban dweller who has lived in three global cities over the past decade, as a politically conscious citizen, and as part of evolveEA, where our own Urban Strategies and Social Engagement projects often intersect with the arts. Use of the term “Neighborhood Change” is an entrée to discussion about issues of urban redevelopment and the good and bad things that can come with it, such as gentrification, economic growth, green building and infrastructure improvements, displacement, changing demographics, and related trends.

Presenters at the conference included both Baltimore-based and national historians and urban scholars, as well as an inspiring mix of artists and art-based initiative leaders. Absorbing some historical and contemporary background on urban change in cities like Baltimore, New Orleans, Washington DC, and Philadelphia had us all examining the role of artists and their art within the context of urban redevelopment. We recognized that young artists often assume the role of urban pioneers when they are some of the first new movers into neighborhoods that historically suffer from institutional neglect, and that this is a problematic attitude because it often leads to redevelopment that excludes or displaces the existing community. By contrast, in a place like New Orleans, musicians and artists are the long-time residents of similar changing districts where they have been or are at-risk of being displaced. Arts districts seem to grow naturally in the more affordable areas of our cities, and in many cases the presence of art and culture in those areas causes real estate value to rise and attracts investment.

A hand-painted essay by Olivia Robinson on the wall at D Center Baltimore articulates issues of race and class that are all too familiar to longtime residents of changing neighborhoods in many American cities (click the image to enlarge)

The Station North Arts & Entertainment District in Baltimore, where the conference was hosted, could be considered a case study of these phenomena. For me (as well as for other Pittsburghers who were in attendance), there are some obvious parallels in certain neighborhoods here in “The ‘Burgh”. In Pittsburgh we have several neighborhoods where the arts have stimulated a revitalization of sorts, and with decades of population decline now pivoting in the other direction, new residents are drawn to these areas. The Penn Avenue Arts Initiative in our own part of the East End is a prime example, and nearby neighborhoods like Lawrenceville and others in Pittsburgh’s North Side have also developed arts-oriented identities.

Some of the innovative and exciting arts-based places we visited in Station North included the Station North Market building, whose owners have worked closely with local artists and designers to transform this historic, previously vacant building into a hub for the arts. Tenants now include Baltimore Print Studios, D Center Baltimore, and The Windup Space. Also in the neighborhood are several live-work art spaces, such as Area 405, which graciously hosted the second day conference sessions, and the CopyCat building, as well as some large institutions like Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), which hosted the conference’s first day sessions in its new graduate studio center.

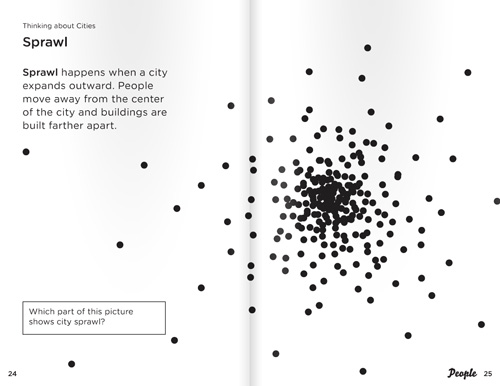

I was also excited to meet designer Becky Slogeris, a graduate of MICA’s acclaimed Social Design graduate program. For Becky’s thesis project, she self-published a wonderful educational tool called The Baltimore Textbook. Available for purchase online for $10, this easy-to-use book lays out some background information on American cities and explores concepts around development, housing, and more using Baltimore as a case study. I found the book’s design engaging in a way that would entertain and educate a young child or an accomplished professional.

A spread from The Baltimore Textbook

A rise in Station North area real estate value is accelerating development, with a recent announcement that the neighborhood’s largest vacant building will be redeveloped to house new spaces for Johns Hopkins University and MICA. And since the Artists and Neighborhood Change conference, local conversation about the roles of artists within their communities has continued to engage city officials, community figures, and residents (listen to this segment from a Baltimore talk radio show, for example).

The conference also highlighted the importance of neighborhood histories and our responsibility to educate ourselves about the communities we inhabit. I think many who are following these issues would agree that community engagement is paramount for developers, artists, and leaders of arts-focused institutions and organizations who locate themselves in existing urban neighborhoods. Discussions focused on history emerged primarily in presentations about the historic U Street corridor in Washington DC and the Tremé neighborhood—of television fame—in New Orleans. Both neighborhoods were, and in a diminished capacity continue to be, centers of African-American musical and artistic heritage. They were among the earliest areas inhabited by free people of color after the abolishment of slavery in the US, and have been targeted for intentional displacement by developers and city officials during more recent periods of development.

A mural and a community garden in Station North, Baltimore, illustrate a profound relationship between art and sustainability in changing urban neighborhoods

It was noted during the conference that the arts and sustainability in contemporary America have in common the effect of bringing about neighborhood change that, when not managed with care and consideration for the voices and needs of community members, makes the displacement of indigenous populations inevitable. In strong-market cities like New York and Washington DC, the past twenty years have seen so much gentrification that the intention of developers would seem to be nothing other than ruthless capitalism. In weak-market cities like Baltimore, Pittsburgh, and Detroit, the slower pace of re-urbanization allows us to learn from the missteps and ill-planning of others. That coupled with the lower density of our cities can also create more viability for economic diversity in housing and retail space. Here, in Pittsburgh, we are working to engage communities around sustainability, while some of our neighbors in the arts are doing the same.

Through evolveEA’s work with the communities of Lawrenceville and Larimer, we are hearing a desire to achieve a balance between sustainable growth in attracting new residents and businesses and the capturing of equity for those who are already in the neighborhood. Some of the organizations in Baltimore are doing a good job of this. During the conference, however, there were some complaints from the local community members about access to schools in the neighborhood. The Baltimore Design School, a new school with a design-centered curriculum is opening this fall. The school and its facilities (including a playground) will not necessarily be open to all of those who live in its vicinity due to the fact that admissions are based on an application and lottery system like all area charter schools use.

Presenters from Dance Place in Washington and the Asian Arts Initiative in Philadelphia demonstrated thoughtful and successful community engagement programming in their presentations at the conference. Here in Pittsburgh, as the pace of development and the arrival of transplants is picking up, there are several arts organizations that either were conceived in order to engage and serve people in their neighborhoods or deserve recognition for doing so:

East End Neighborhoods

- Assemble [Garfield]

- Irma Freeman Center for Imagination [Garfield]

- Union Project [Highland Park]

- Art House [Homewood]

- Kelly Strayhorn Theater [East Liberty]

North Side

- AIR (Artists Image Resource) [East Allegheny]

- New Hazlett Theater [East Allegheny]

- Mattress Factory [Mexican War Streets]

- The Charm Bracelet Project